Community Portraits:

Ecological stories, struggles and sorrow in artist Carolina Caycedo’s ‘Cosmotarrayas’

Kuhu Kopariha

Carolina Caycedo Land of Friends installation view. Photo: Tom Nolan, © 2022 BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art

Introduction

Cosmotarrayas (2015 -) are a series by Mestiza artist Carolina Caycedo,[i] of suspended fishnet installations, often spray painted or dyed, enveloping symbolic objects collected through fieldwork. The word Cosmotarraya is an amalgam of two words ‘cosmos’ and ‘atarraya’ (Spanish for net) whose meanings combine to expose the universe sustained with and through the net in the fishing community, many of whom have been displaced due to the construction of large dams in Colombia.[ii] These artworks are an extension of Caycedo’s larger series Be Dammed/ Represa (2013-), a series of multimedia works centred around the construction of 15 hydroelectric dams fracturing the flow of Colombia’s largest river, Yuma or Magdalena. Over the years, the ongoing project branches out to raise concerns over other damming projects in Latin America, and privatisation of water bodies in Germany, USA, and the UK.[iii] The artist’s goal is to resist the commodification and destruction of non-human entities in her capacity as a cultural contributor. She wants to achieve this by employing interdisciplinary approaches by incorporating local and indigenous points in her artistic outputs.

In the last decade, multiple exhibitions and subsequent catalogues have been produced on the diverse, multimedia works of Carolina Caycedo, criticising ‘Extractivism’[iv] in Latin America specifically and the concept of ‘Capitalocene’ in general.[v] Special interest has been showcased towards the Cosmotarrayas for their unique visuality and their stories, histories, memories, and the identities of indigenous communities and non-human entities. These are Nations, peoples, and bodies usually marginalised in art galleries and academic spaces.[vi] Yet, the scope of the artist’s work has overshadowed individual Cosmotarrayas and detailed study of their aesthetics, materials, and narratives representing decoloniality and indigeneity. Also partially responsible for the aforementioned absence is that art historical knowledge on the artist is still in its nascent stage, especially as the development of Cosmotarrays is still ongoing.

In this essay, I read the Cosmotarraya Yuma (2015), personifying the Colombian river, people, and the effects of the damming project. This is one of Caycedo’s first interpretive fishnet sculptures. I place Yuma within its specific social context, investigate its visual language, and explore the universal themes underpinning the sculpture.

Caycedo views the installations as “talismanic objects that cast a visual spell”. These objects are crucial in bridging two streams of her artistic practice - community based research or performances and private studio practice.[vii] Thus, the development of the Cosmotarrayas’ visual language, and how it challenges existing aesthetics and art spaces, are important art historical considerations. Additionally, I will showcase how the ‘Cosmonets’ are portrayals of contradictory ideas - simultaneously hyper local and global, decolonial and colonial, grief stricken and hopeful.

Yuma: Undermining the Extractive View

Cosmotarraya Yuma (Fig. 1) was amongst the first three sculptures created by the artist, all made using the nets gifted to her by artisanal fisherwoman and activist Zoila Ninco. The three river portraits, as the artist calls them, appear together in an installation view in Instituto de Visión, Bogota, Colombia (Fig. 2). Here we see, Yuma (Colombia), Yaqui (Mexico), and Elwha (Washington, US) from right to left, and together they personify not only the rivers but also the indigenous people who named these water bodies. Yuma, Yaqui, and Elwha are objectual outputs of Carolina’s 2015 performance One Body of Water in Los Angeles, where three actors/collaborators portrayed themselves as rivers, giving the non-human bodies personhood. Carolina herself played Yuma, manifesting the struggle against the ‘Master Plan’ dam development which would restrict the natural flow of the water fifteen times. She chose an actor to personify the river Yaqui to display the effects of the extractive and capitalistic projects, the privatisation of the river had resulted in drying the rivers mouth and adversely affecting eight Yaqui villages. And finally, Elwha was chosen to demonstrate the effects of resistance and restoration, the river’s natural flow and fisheries returned to the water body after two large scale-dams were removed. The actors gave voices to the rivers and employed objects and oral narratives of the indigenous communities. These objects along with the atarrayas received from Zoila Ninco are the basis for the construction of sculptures Yuma, Yaqui, and Elwha in Figure 2.[viii]

Figure 1: Cosmotarraya Yuma by Carolina Caycedo, 2015

The atarrayas can be seen hanging from the ceiling of the gallery space, mimicking the way they are suspended from trees to airdry, (Fig 3) after working long shifts in the hands of a fisher.[ix] Their conical shape is altered by the objects placed inside them, creating varying shapes and sizes. The (shared and distinct) heritage of the indigenous communities of the Americas is represented by objects like wool and cotton poncho, leather sandals (Huaraches), sage and musical instruments.[x] In Yuma, the artist dyes the centre of the net or the top quarter of the conical shape in red and leaves the rest in its original white. Two colourful wool-wrapped wooden sticks are fixed in the weaves of the net horizontally, at different heights. Their placement disrupts the natural conical fall into the shape of a voluminous four-edged star. From the sticks hang the ribbon, lead weights, dry chile peppers, dry sage, cotton poncho and Huaraches (leather sandals), used and worn by Carolina during One Body of Water (Fig. 4).

Figure 2: Installation View at Entre Caníbales, Instituto de Visión, Bogota, Colombia, 2016 (From left to right, Elwha, Yaqui and Yuma)

Figure 3: Cast fishing nets hanging from trees drying on the riverbank in front of Carlos Wilfredo Hernandez’s shack, Magdalena River, Colombia

Figure 4 One Body of Water, Performance by Carolina Caycedo and actors, 2014 (Carolina as Yuma)

Through artworks like Yuma, Caycedo succeeds in creating a contemplative image of the Anthropocene. She uses ordinary everyday objects and steers away from the previously established visual language which produces shock, dread and sensationalism. During the 2010s, other artists working on the theme of climate change produce paintings, photographs or documentary films which either highlight the documentation of wildlife, which often serves to conceal ongoing destruction of wildlife; or aesthetically beautiful compositions of extractive practices which undermine their destructive capabilities.[xi] Carolina breaks these automations by showcasing previously submerged points of view in her film, digital, and performance art, as discussed by writer and scholar, Macarena Gómez-Barris in The Extractive Zone. In her 2014 film Land of Friends (Fig. 5), the artist showcases the destruction caused by one particular dam called El Quimbo, shot in what Gómez-Barris calls the ‘fish-eye perspective’ by submerging the camera int the muddy water.[xii] This fish-eye view is one of the many ways her film stands oppositional to other environmental artists like Canadian photographers and filmmakers such as Edward Burtynsky, Jennifer Baichwal, and Nicholas de Pencier, who are part of the Art Gallery of Ontario’s ‘Anthropocene Project’. Their film work (Fig. 6) has produced some of the most breath-taking views of extractive practices such as mining sites, forest fires and natural death. Unlike these documenters, Caycedo’s Land of Friends, gives us the site of the El Quimbo dam all but twice in her 38-minute film. Instead she focuses on the visuals and voices of landscape and community, and the relationship between them. However, she is not alone in drawing these parallels. The genre is developing and beginning to include artists from the global majority who situate rivers as part of the cultural life of the region.[xiii] Caycedo is unique in the way she subdues the western ‘documentary’ style by portraying the non-human landscape as a feeling and thinking entity.[xiv]

Figure 5 Screengrab showcasing the fish-eye perspective from Land of Friends by Carolina Caycedo,, 2014

Figure 6: Screengrab from the Anthropocene Project by Jennifer Baichwal, Nicholas de Pencier and Edward Burtynsky, 2018

The dynamic points of view of water, fish, and local human cohabitants are brought to the fore through the Cosmotarrayas’ and particularly in Yuma. The way Cosmonets envelope the objects, for instance, constricts our view of the materials and invokes the perspective of the fish. In Yuma, the net is handmade carrying ancestral knowledge of weaving, rivers, and fish passed down through oral narration. Caycedo uses objects gifted by local fisherwoman Zoila Ninco, to embed the knowledge she possesses and shares. In addition, the natural fall and porous quality of the net portrays the flow of the river. According to Caycedo, the porous and malleable structure of the net contests the concrete and forceful nature of the dam.[xv]

The making visible of submerged perspectives reflects decolonisation, yet the artist layers these narratives by incorporating other challenging objects like red chile peppers and cotton. Although the purpose of these objects was different when used in the One Body of Water performance, their material presence in Yuma transforms them into symbols of colonialisation and globalisation. Both cotton and chile peppers were native to Central and South America and considered highly important in local cultures.[xvi] The commercial cultivation of the crops and their subsequent export across the world transpired after the invasion of Christopher Columbus in the fifteenth century.[xvii] Additionally, these now global objects frame a narrative of relationality between the tropical souths, where they are used for commercial cultivation, and the global north, where these materials are now inextricably linked to their cultural identities. According to anthropologist Zoe Todd, any indigenization of the Anthropocene displays ‘mutual sacrifice and relationality’ to sabotage colonial practices. Artist Carolina Caycedo’s Yuma perfectly illustrates this.[xviii]

She even layers objects that display relationality between human and non-human entities as discussed earlier. Apart from the fishing nets, this relationship is evoked through other objects - like the dried sage and huaraches. The former is used in traditional medicine practices, and the latter is a handmade sandal created from natural materials like wood & leather, emblematic of indigenous knowledge systems. These sustainable practices that continually borrow from plant and animal matter are ever-present in the cultural fabric of the local populations. Thus, Yuma is embedded with the Colombian view of landscape as a ‘cultural artifact’ - a tapestry of ideas, meanings and practices incorporating continuity between the past, present and future.[xix]

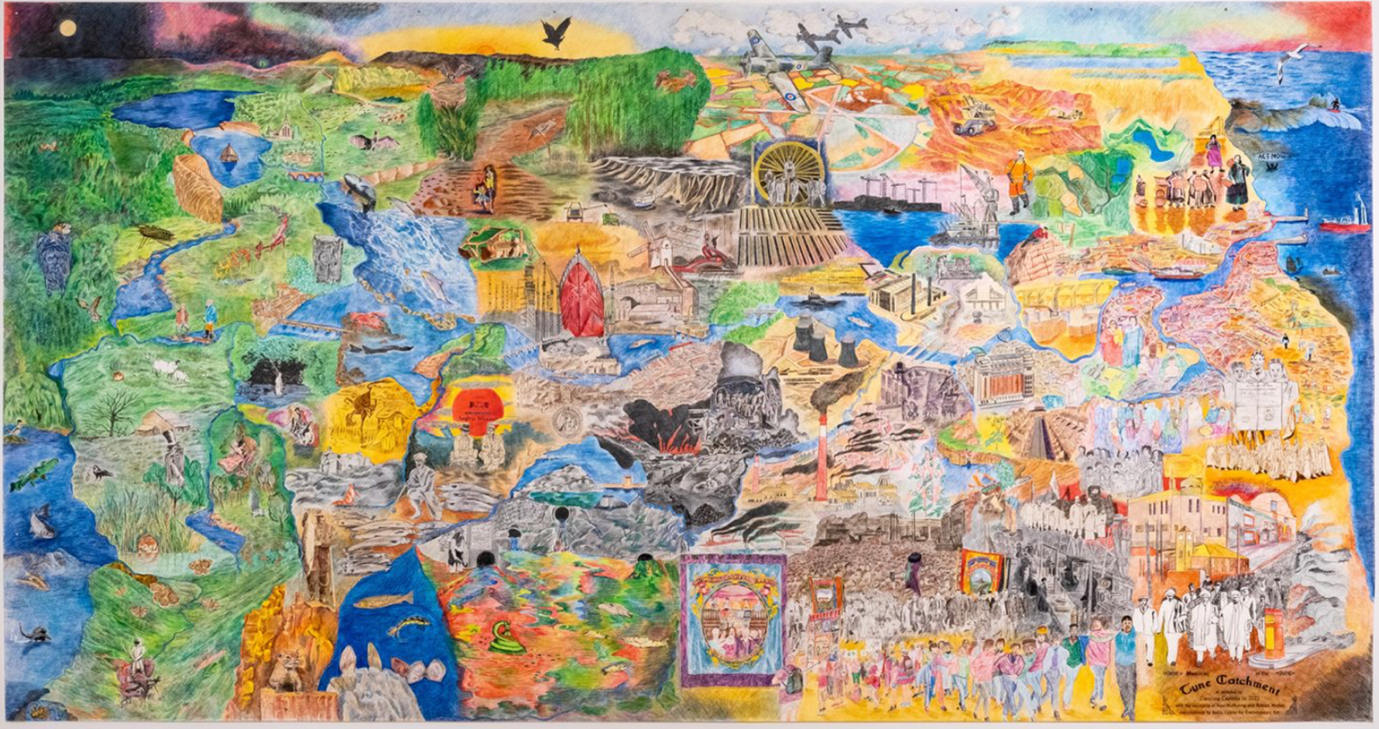

Caycedo’s layered perspective in Land of Friends and Cosmotarrayas allow artworks to be situated within their local and specific context, whilst simultaneously presenting global anxieties regarding climate change and environmental justice. As seen above, the artists’ practice is engaged with fieldwork and excavating oral histories across borders. This introduces a transnational dimension to her practice. In her 2023 exhibition Land of Friends, at the Baltic in Newcastle (UK), Caycedo presented an overview of her practice alongside a new commission titled Tyne Catchment (Fig 7). This colourful pencil drawing on paper is a response to the in-depth research conducted locally into the Tyne catchment area. In 2021, Rose McMurray was commissioned specifically for the exhibition to investigate the life of this river flowing a few meters from the Baltic.

Figure 7: Tyne Catchment (2022) by Carolina Caycedo, captured by Tom Nolan, © Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art

We follow the journey the Tyne takes from Alston and the Kielder and Derwent reservoirs to its meeting with the North Sea. This journey is populated with historical and contemporary events that reflect the relationship the local communities have with the Tyne Catchment area. Like in Yuma, Caycedo is critical of the Tyne’s industrial past, showcasing the Stella Power Station which stood as a landmark in the Tyne Valley for 40 years. This is the major reason for the pollutants in the South Tyne and the cause of salmon dying – as is showcased in the drawing. The salmon appear floating in a poisonous puddle that runs from open pipes into the river. Around these scenes of death and destruction, the artist showcases moments of resistance, such as the Durham’s Miner’s Gala (1871 - present) and the Suffragette movement (with Newcastle and District Women’s Suffrage Society est in 1900). In contrast to these populated scenes, the west part of the drawing showcases green forests, wetlands, and the wildlife that surrounds them. Several of the stories depicted in the drawings directly reference archival photographs and oral histories gathered from the local communities connected to the river (fisherfolk, river restoration workers and leisure groups).

Many different periods are present within the Tyne Catchment. At the top we see the skies representing different times in a day from dawn to a full moon night. In the middle we witness historical developments with the construction of bridges and mining sites alongside their contemporary consequences of pollution and the need for preservation as demonstrated by the green and luscious Kielder Forest. The forest stands as a real and imagined world where wildlife sprawls but also exists within the boundaries defined by us. This provokes us to understand and question this changing natural balance. This idea is enhanced as the viewer stands under the fishnets hanging from the ceiling of the Baltic, once again offering a fish-eye perspective. This reflective, contemplative, and gentle notion of time challenges other artists’ practice. For example Olafur Eliasson[xx], who is one of the most recognised climate action artists. Olafur’s 2015 installation Ice Watch (Fig. 8), placed outside the Place du Panthéon in Paris, is reminiscent of the sensationalism of death and destruction of The Anthropocene Project (Fig. 6).

Figure 8: Installation view at Place du Panthéon, Paris, Ice Watch by Olafur Elaisson, 2015

Ice Watch was made up of twelves ice blocks arranged in a circle, emulating the design of a ‘ticking’ clock. In this watch, the passage of time is calculated through the melting ice, bringing the audience face-to-face with the effects of global warming. These immense blocks of ice were gathered free floating icebergs, detached from the Greenland ice sheet due to the changing climate. Eliasson secured the ice blocks with the help of geologist Minik Rosing and brought them to various sites in Europe between 2014-2018.[xxi] The intention behind the work was to “make climate challenges we are facing tangible…. [and] inspire shared commitment to climate action.”[xxii] Across the sites, people were able to engage with the Arctic and its changing natural landscape because of human interventions. However, despite the artist’s best intentions and the participatory and communal approach, the ethical considerations of Eliasson’s artistic productions problematise the installation piece.[xxiii]

The active displacement of natural bodies of floating ice and their use in awareness raising plays into dominant, often western, narratives in the study of climate change. Where the onus of climate action is placed on the individual and his/ her/ their carbon footprint, instead of focusing on large-scale governments and corporations that create ecological and humanitarian crises simultaneously. Eliasson is unconcerned by the removal of the ice blocks from their natural habitat because of the view that nature is for us to take, view, dissect and study. Here again justifications of its dispossession are given by calculating the relatively low carbon footprint generated in the transportation and installation of the Ice Watch.[xxiv] This desperate need to ‘see’ and duplicate natural beauty is also reminiscent of ecotourism, only here the nature is brought to us. Philosophers like Lisa Kretz and Susan Sontag have expressed the gap between awareness (visual or otherwise) and action.[xxv]

Moreover, the attraction of the installation also lies in its technological innovation - the geoscientist’s ability to fish out ice blocks and transport them on site via fridge containers.[xxvi] There is irony in perpetuating shallow ecological narratives focused on pollution whilst incorporating the kind of technology which gave rise to the climate crisis. By providing repeated references to community and indigeneity and placing these concerns at the works’ centre, Carolina’s Land of Friends, Yuma and Tyne Catchment undermine established colonial extractive views. She circumvents the manifold paradoxes that are almost deeply rooted in eco-aesthetics and/or environmental art and creates a new visuality of layered subjectivities. They then deal with considerations of non-human bodies regardless of their beauty or their ability to provide pleasure and excitement.

[i] Latin, mestiza Caycedo was born in 1978, London. She went back to her parent’s home Bogota, Colombia at age 6 and spenf her growing years there. She currently lives and works in the United States.

[ii] Carolina Caycedo and Jeffrey D Bloise, “The River as Common Good: Carolina Caycedo’s Cosmotarrayas” Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston (Curatorial Note), 2020, Accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.icaboston.org/publications/river-common-good-carolina-caycedos-cosmotarrayas

[iii] Acevedo-Yates, Carla, “Embodied Spiritual Framework” in Carolina Caycedo: From the Bottom of the River, (New York: DelMonico Books, 2020) 23-34

[iv] Extractivism is defined as an intense resource extraction with largescale destruction of the environment, historically characterised by colonial or capitalist developmental of the developed North extracting from the developing South.

Manuela L. Picq, “Resistance to Extractivism and Megaprojects in Latin America”, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. 2020

[v] Capitalocene is the term used for Anthropocene bringing focus to neo-colonial capitalism impact on the climate. For the rest of the essay, I use the term Anthropocene.

[vi] Todd, Zoe. “Indigenizing the Anthropocene” in Art in the Anthropocene, ed by Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, 131-140. (London: Open Humanities Press, 2015) 245

[vii] Video Interview from “Carolina Caycedo: Land of Friends”

[viii] Carolina Caycedo and Jeffrey D Bloise, “The River as Common Good: Carolina Caycedo’s Cosmotarrayas”

[ix] Acevedo-Yates, Carla, “Embodied Spiritual Framework” 32-33

[x] Catalogue Entry, Carolina Caycedo “Carilna Caycedo”, Accessed April 20, 2023 http://carolinacaycedo.com/cosmotarrayas-comotarrafas-series-2016

[xi] Irmgard Emmelhainz, “Images Do Not Show: The Desire to See in the Anthropocene” in Art in the Anthropocene, ed by Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, 131-140. (London: Open Humanities Press, 2015)

[xii] Macarena Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017) 101

[xiii] May and Reuben Fowkes, “River Ecologies” in Art and Climate Change (World of Art), (London: Thames and Hudseon, 2022) 124

[xiv] Gómez-Barris, The Extractive Zone, 13-15

[xv] Carolina Caycedo and Jeffrey D Bloise, “The River as Common Good: Carolina Caycedo’s Cosmotarrayas”

[xvi] George McCutcheon McBride, “Cotton Growing in South America.” Geographical Review Vol 9 (1920). 35–40.

[xvii] Simon Richardson, “Chilli Peppers: Global Warming” The Time. June 14, 2017

[xviii] Todd, Zoe. “Indigenizing the Anthropocene” 248

[xix] Virginia García Acosta, The Anthropology of Disasters in Latin America, (London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2020) 87

[xx] The comparison can be made because Carolina is a transnational individual and has been showcasing artworks in Europe.

[xxi] J. Roosen Liselotte, Christian A. Klöckner & Janet K. Swim, “Visual Art as a way to communicate Climate Change: A Psychological Perspective on Climate Change” World Art Vol 8 (2), 17-19

[xxii] Ted Nannicelli, “The Interaction of Ethics and Aesthetics in Environmental Art”. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 76, no. 4 (2018): 498

[xxiii] J. Roosen Liselotte, “Visual Art as a way to communicate Climate Change”. 19

[xxiv] “Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing Ice Watch” Tate Modern Exhibition, 2018, Accessed April 20, 2023 https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/olafur-eliasson-and-minik-rosing-ice-watch

[xxv] Rick Crownshaw, “Mourning nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief” American Imago, 77(1), 245.and Irmgard Emmelhainz, “Images Do Not Show”. 135

[xxvi] Tim Jonze, “Icebergs ahead! Olafur Eliasson brings the frozen fjord to Britain” The Guardian, Dec 11, 2018, Accessed April 20, 2023 https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/dec/11/icebergs-ahead-olafur-eliasson-brings-the-frozen-fjord-to-britain-ice-watch-london-climate-change

Bibliography

Acevedo-Yates, Carla. Carolina Caycedo: From the Bottom of the River. New York: DelMonico Books, 2020

Baltic. “Carolina Caycedo: Land of Friends” 2022. “Accesses April 20, 2023 https://baltic.art/whats-on/i-carolina-caycedo-land-of-friends/ ”

Carvalho, Délton Winter de. “The Ore Tailings Dam Rupture Disaster in Mariana, Brazil 2015: What we have to learn from Anthropogenic Disasters.” Natural Resources Journal 59, no. 2 (2019): 281–285.

Cayecedo, Carolina. And Jeffrey D Bloise. “The River as Common Good: Carolina Caycedo’s Cosmotarrayas” Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston (Curatorial Note), 2020. “Accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.icaboston.org/publications/river-common-good-carolina-caycedos-cosmotarrayas

Caycedo, Carolina. Portfolio “Accessed April 20, 2023 http://carolinacaycedo.com/

Crownshaw, Rick. “Mourning nature: Hope at the Heart of Ecological Loss and Grief” ed. by Ashlee Cunsolo and Karen Landman (review). American Imago, 77 (1), 232-245.

Emmelhainz, Irmgard. “Images Do Not Show: The Desire to See in the Anthropocene” in Art in the Anthropocene, ed by Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, 131-140. London: Open Humanities Press, 2015.

Fowkes, May and Reuben. “River Ecologies” in World of Art: Art and Climate Change ed by Maya and Reuben Fowkes, 122-124. London: Thames and Hudseon, 2022.

García Acosta, Virginia. The Anthropology of Disasters in Latin America, 1-21, 82-90. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2020.

Gómez-Barris, Macarena. The Extractive Zone, 1-17; 67-91. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017

Gruber, Max. “Carolina Caycedo’s Cosmotarrayas and the Spirit of the River” Charge Magazine (review). c. 2018

Jonze, Tim. “Icebergs ahead! Olafur Eliasson brings the frozen fjord to Britain” The Guardian, Dec 11, 2018, Accessed April 20, 2023

L. Picq, Manuela. “Resistance to Extractivism and Megaprojects in Latin America”. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press, 2020

Liselotte J. Roosen, Christian A. Klöckner & Janet K. Swim, “Visual Art as a way to communicate Climate Change: A Psychological Perspective on Climate Change”. World Art Vol 8 (2).

McBride, George McCutcheon. “Cotton Growing in South America.” Geographical Review 9, no. 1 (1920): 35–40.

Nannicelli, Ted. “The Interaction of Ethics and Aesthetics in Environmental Art”. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 76, no. 4 (2018): 497–506.

Richardson, Simon. “Chilli Peppers: Global Warming” The Time. Edited: June 14, 2017

Tate, “Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing Ice Watch” Tate Modern Exhibition, 2018, Accessed April 20, 2023 https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/olafur-eliasson-and-minik-rosing-ice-watch

Todd, Zoe. “Indigenizing the Anthropocene” in Art in the Anthropocene, ed by Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, 131-140. London: Open Humanities Press, 2015.

Kuhu Kopariha is an independent researcher and creative professional from India, currently based in London. She is currently engaged with organisations - Art South Asia Project (ASAP) as a Programme Manager and the Archive of Modern Conflict (AMC) as research consultant. She specialises in generating new research and curating modern and contemporary art, with a focus on South Asian modern and contemporary practices. Her work engages with the developing topics and methodologies related to contemporary arts and cultural landscape, engaging with themes of decolonisation, art and the anthropocene, community research as art practice, to name a few. She has previously worked for the Sarmaya Art Foundation (Mumbai, India), York Art Gallery (York, UK) and Artist Charles Fréger (France). She has an MA in History of Art (Modern & Contemporary Pathway) from the University of York.